![]() Economia e Energia – http://ecen.com.br

Economia e Energia – http://ecen.com.br

Nº 105, outubro a dezembro de 2019

ISSN 1518-2932 Disponível em: http://eee.org.br e http://ecen.com (números anteriores)

Palavra do Editor:

O TNP Completa 50 anos, devemos ratificar o TPAN

A Organização das Nações Unidas foi estruturada de uma maneira pragmática onde os países mais poderosos, os que se consideraram os vencedores da Segunda Guerra Mundial, reservaram para si o poder de veto no Conselho de Segurança.

A tradição diplomática brasileira, pelo menos até o Governo Bolsonaro, optou por prestigiar as organizações multilaterais e, ao invés de combater a desigualdade de direito entre as nações, dedica seus esforços a conseguir o destaque que o País se julga merecedor, inclusive o direito de ser membro permanente do Conselho de Segurança. Fundamentalmente, o Brasil concorda com o princípio não igualitário da Organização, mas considera que sua importância entre as nações ainda não foi adequadamente reconhecida.

Mesmo sem alcançar êxito pleno, o Brasil conseguiu um lugar de destaque no Sistema ONU, com participação importante em órgãos diretivos, e se firmou como um ator importante no conjunto de organizações que compõem o Sistema.

No que tange as armas nucleares, o Brasil manteve uma atuação coerente de defender os usos apenas pacíficos da energia nuclear e seu direito de desfrutar dos benefícios científicos e tecnológico dessa energia e defende, coerentemente, uma política efetiva de desarmamento nuclear.

Dentro da coerência desses princípios, o Brasil recusou, desde o início, o Tratado de Não Proliferação Nuclear. Acabou aderindo a ele, apesar de continuar a considerá-lo discriminatório. Antes, já havia firmado acordos que proibiam atividades nucleares não pacificas e colocou, em sua própria Constituição, o compromisso de que suas atividades nucleares seriam exclusivamente pacíficas. Recentemente, o Brasil teve papel importante na proposição e aprovação pela Assembleia da ONU do Tratado de Proscrição de Armas Nucleares – TPAN, que visa banir, sem discriminação, todas as armas nucleares.

Urge agora ratificá-lo.

Carlos Feu Alvim

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Sumário

O TNP ESTÁ FAZENDO CINQUENTA ANOS DE VIGÊNCIA, NADA A COMEMORAR

A Conveniência de Ratificar o TPAN

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Opinião:

O TNP ESTÁ FAZENDO CINQUENTA ANOS DE VIGÊNCIA, NADA A COMEMORAR

Carlos Feu Alvim e Olga Mafra

Resumo

O Tratado de Não Proliferação Nuclear – TNP foi concebido para limitar o número de países com armas nucleares. Ele está completando, em 2020, cinquenta anos de vigência. Não há muito a comemorar.

O Tratado, que o Brasil sempre considerou discriminatório, divide os países em com armas nucleares e sem armas nucleares.

Aos primeiros consagra o direito de manterem as armas nucleares e aos demais veda esse direito e os sujeita a um sistema de verificação de todos os materiais e instalações nucleares pela AIEA.

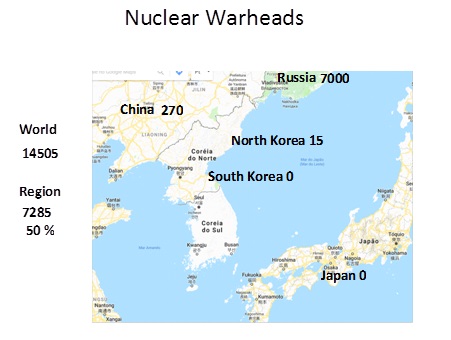

Os cinquenta anos de vigência do TNP são uma oportunidade de avaliar seus resultados que não foram eficazes. De fato, o número de países possuidores de armas nucleares quase dobrou e os arsenais cresceram notavelmente até o final dos anos oitenta do século XX.

Os tratados de redução de armas, ocorridos pós distensão entre EUA e a extinta União Soviética, estão sendo abandonados ou prescreveram. Em todos os países nuclearmente armados estão em curso programas de modernização do arsenal nuclear, o que torna improvável qualquer programa sério de desarmamento.

Apesar disso, não parece oportuno abandonar o TNP e o Brasil deve usar seu prestígio para exigir compromissos de desarmamento dos nuclearmente armados nele previstos.

Quanto ao Tratado sobre a Proibição de Armas Nucleares – TPAN, o Brasil deveria ratificá-lo, reafirmando seus esforços na ocasião de sua aprovação pela Assembleia Geral da ONU. O TPAN não se opõe ao TNP, mas tem as vantagens de não ser discriminatório e de criar uma maior pressão pelo desarmamento.

Palavras Chave:

TNP, TPAN, não proliferação nuclear, armamentos nucleares, desarmamento, proliferação nuclear

____________

O TNP

O Tratado de Não Proliferação Nuclear – TNP (UN, 2015), completará 50 anos de vigência em 6 de março de 2020[1]. Pelo que nele foi acordado, os cinco países membros permanentes do Conselho de Segurança (P5) atribuem-se abusivamente ao direito de continuar a possuir armas nucleares e os demais renunciam a elas e se comprometem a submeter suas instalações e materiais nucleares a inspeções internacionais pela AIEA, podendo sofrer punições se não cumprirem com as determinações do Tratado.

É, sem meias palavras, um tratado de submissão, em assuntos nucleares, dos países não possuidores de armas (NNWS), aos países possuidores de armas nucleares (NWS)[2].

As compensações oferecidas aos não nucleares (NNWS) foram irrisórias, os países nucleares (NWS) apenas se comprometeram a buscar “com boa fé”[3] o desarmamento. Não foi fixado prazo, nem data para alcançá-lo, nem limite para os arsenais e nem ao menos foi assumido o compromisso dos possuidores de armas nucleares de não as usar contra os desarmados. No que concerne ao acesso à tecnologia, as partes se comprometem a compartilhar “da maneira mais completa possível”[4] os equipamentos, materiais e informações científicas e tecnológicas para o uso pacífico da energia nuclear onde a definição do possível é, obviamente, dos fornecedores que, inclusive, criaram posteriormente um “clube” para definir esses critérios[5].

A ausência da promessa do não uso das armas nucleares contra os não nucleares ressalta, ainda mais, a natureza discriminatória do Tratado. A doutrina dos EUA sobre armas nucleares chegou a estabelecer, em 1978, um comprometimento que teoricamente até protegia os desarmados. Ela foi modificada pelo presidente W. Bush no sentido de considerar essa possibilidade de uso, não foi revogada pelo presidente Obama e, recentemente, o atual presidente Trump ampliou o leque de circunstâncias em que poderia ser usado o armamento nuclear (Panda, 2018).

O Brasil, por quase 30 anos, rejeitou o TNP por considerá-lo discriminatório e porque já havia assinado anteriormente (1967) o Tratado de Tlatelolco (Opanal Inf. 14, 2015) no qual renunciava ao uso e posse de armas nucleares. Tlatelolco tem protocolos adicionais, assinados (com algumas ressalvas) pelos países nuclearmente armados e aqueles que têm, de fato ou de direito, possessões na área, que preveem o compromisso de não agressão.

Muitos argumentam, em favor do TNP, que ele teria evitado a repetição da tragédia de novo uso das armas nucleares. Ora, as armas foram usadas quando não havia proliferação e os EUA tinham certeza da não retaliação nuclear o que evitou novas tragédias nucleares, até agora, foi justamente a proliferação inicial para alguns países e o sistema de aliança de proteção entre os integrantes dos dois grandes grupos políticos em que o mundo se dividiu no pós Segunda Guerra Mundial. O equilíbrio pelo terror da mútua aniquilação tornou inviável a guerra em que os dirigentes, na retaguarda, enviavam à frente de batalha seus jovens ao sacrifício, em defesa de suas propriedades e família. Na guerra nuclear elas estariam em perigo imediato.

Quanto aos resultados da não proliferação, pode-se dizer que o Tratado não foi eficaz; o número de possuidores de armas nucleares quase dobrou, sendo agora nove os países nuclearmente armados. A contenção no número de países integrantes do grupo dos nuclearmente armados deve ser muito mais atribuída ao sucesso de programas como o “Átomos para a Paz” que propriamente ao TNP. Este programa, lançado pelo Presidente Eisenhower em 1953, portanto 15 anos antes do TNP, permitiu aos países o acesso a usos pacíficos da energia nuclear sem passar pelo domínio das tecnologias de enriquecimento e reprocessamento que possibilitam a proliferação. Ele serviu ainda para amadurecer o processo de salvaguardas da AIEA que se restringia, nesses casos, aos equipamentos e material nuclear fornecidos.

Ainda sobre o equilíbrio pelo terror, os acordos de proteção tipo “guarda-chuva”, em que uma potência nuclear assegurava proteção nuclear a alguns países diretamente ameaçados, também evitou que houvesse a proliferação nesses países. Japão e Alemanha, são exemplos de países em que a proliferação de armas nucleares foi, até hoje, assim evitada.

As iniciativas bilaterais de redução e limitação de armas também obedeceram a esse temor da destruição mútua criado pela ameaça nuclear. Durante algum tempo, essas iniciativas propiciaram algum alívio à população mundial. Elas foram apresentadas como moeda de troca com os NNWS nas revisões do TNP, mas pouco têm a ver com o Tratado já que, em nenhuma delas, foi incluído o estrito controle internacional previsto no Artigo VI do TNP.

Nas condições atuais, os tratados de limitação de armas estão paulatinamente sendo desativados e novos tipos de armas e lançadores estão sendo desenvolvidos pelos nuclearmente armados. Entre as novidades, o aperfeiçoamento de armas táticas, de menor custo e poder de destruição, se encaixa perfeitamente no propósito de uso limitado contra países não possuidores de armas nucleares.

Já nos países que interromperam o processo que poderia levá-los ao armamento nuclear, como Brasil e Argentina, ou que renunciaram a ele, como a África do Sul, o sucesso deve ser atribuído à redução de tensões regionais e ao estabelecimento de zonas livres de armas nucleares. Por uma razão semelhante, mas adotando uma outra linha de raciocínio, a Suécia decidiu abandonar seu programa de armas nucleares defensivas por considerar que declarar-se neutra entre os dois blocos era sua melhor defesa.

A desconfiança da eficácia das salvaguardas do TNP, por outro lado, foi impropriamente usada como motivação para guerras contra o Iraque e a Líbia, com pretexto de eliminação de programas nucleares bélicos- e armas de destruição em massa, mas que tiveram como objeto a posse do petróleo e gás, mesmo motivo de outras tantas guerras. A tensão no Irã tem motivos parecidos, embora a questão nuclear possa estar mais explícita.

No caso de Brasil e Argentina, o êxito do processo de desnuclearização se deu evitando cuidadosamente o TNP. No início dos anos noventa, Brasil e Argentina e, parcialmente o Chile, se engajaram em um processo que incluiu: 1) fazer alterações no Tratado de Tlatelolco para colocá-lo em vigor, 2) assinar um Tratado Bilateral, em Guadalajara no México, onde Brasil e Argentina assumem os mesmos compromissos de não proliferação do TNP e criam uma agência de fiscalização mútua, a ABACC, 3) assinar um acordo dos dois países e ABACC com a AIEA, o Quadripartite, aplicando as mesmas salvaguardas abrangentes do TNP.

Com isso, Brasil e Argentina assumiram os mesmos compromissos do TNP de maneira independente sem reconhecer o monopólio nuclear dos cinco membros do Conselho de Segurança da ONU, os P5. Isto ocorreu pela feliz coincidência, na época, da ocorrência de dois governos civis no Brasil e na Argentina

Foi um primoroso trabalho diplomático e técnico[6] que resultou em um arranjo cujos efeitos práticos eram os mesmos do TNP, sem seu caráter discriminatório. Esse arranjo serve de exemplo, ainda hoje, para outras regiões do mundo interessadas em afastar a ameaça nuclear.

Em junho de 1997[7] durante o Governo do Presidente Fernando Henrique Cardoso, o Brasil assinou o TNP, estribando-se num dispositivo constitucional que compromete o Brasil ao uso exclusivamente pacífico da energia nuclear. Acontece, que essa determinação constitucional já estava confirmada em compromissos internacionais anteriores que incluíam o mesmo regime de salvaguardas abrangentes aplicadas pela AIEA aos países não nuclearmente armados signatários do TNP. Por outro lado, nada em nossa Constituição nos obriga a legitimar a posse de armas nucleares por outros países e assinar um tratado que o Brasil continuou considerando discriminatórios, mesmo após sua assinatura.

Essa adesão ao Tratado foi feita sem nenhum anúncio público prévio e sem consulta à Sociedade Brasileira. Alegava-se (Jornal Estado de S. Paulo. 21 de junho de 1997) que, isso se fazia em obediência ao dispositivo constitucional e o Brasil facilitaria, com essa assinatura, sua inclusão como membro permanente do Conselho de Segurança. Pura ilusão, como se verificou nos anos seguintes. Hoje a Índia, que na época não admitia a posse de armas nucleares (teria apenas realizado explosões pacíficas), se declarou possuidora de armas nucleares e está muito mais próxima dessa posição permanente no Conselho do que o Brasil.

Para outros países deve-se reconhecer, que o TNP, conjugado com a pressão diplomática e econômica, pode ter contribuído para que não aumentasse, além dos nove, o número de países armados.

No caso de Brasil-Argentina, na nossa opinião, não vale a pena, a esta altura, romper com o TNP. Estaríamos dando um sinal equivocado quanto à nossa firme intenção de uso somente pacífico da energia nuclear que, no caso do Brasil, está registrado na constituição. Também não há razão de comemorar seu cinquentenário.

Na próxima conferência de revisão do Tratado, entre 27 de abril e 22 de maio de 2020, devemos insistir no cumprimento de suas cláusulas de desarmamento. Não faz também sentido a pretendida prorrogação indefinida sem que as nações nuclearmente armadas apresentem um plano verificável e com horizonte definido de alcançar o desarmamento. Não é aceitável que a Assembleia Geral da ONU conceda a cinco países a permissão, por tempo indeterminado, de manter um arsenal capaz de destruir a Humanidade.

Um fato importante na questão das possíveis modificações do TNP é que “qualquer emenda a este Tratado deverá ser aprovada pela maioria dos votos de todas as Partes do Tratado, incluindo os votos de todos os Estados nuclearmente armados Partes do Tratado e os votos de todas as outras Partes que, na data em que a emenda foi circulada, sejam membros da Junta de Governadores da Agência Internacional de Energia Atômica. (tradução oficial do Artigo VIII §2 do TNP)[8]. Ou seja, o Brasil, enquanto membro da Junta de Governadores, tem uma espécie de poder de veto sobre as emendas do Tratado. Com efeito, este parágrafo estabelece que qualquer emenda, além de precisar de ser aprovada pela maioria dos votos da Assembleia Geral, tem que incluir a aprovação de todos os membros da Junta de Governadores. Isso já inclui os NWS, mesmo que não fosse explicitado, no Artigo, e alguns os outros países.

Ou seja, talvez a única vantagem que o Brasil teve em assinar o TNP é que ele passou a ter uma espécie de “poder de veto” sobre as modificações do Tratado, devido à sua condição de membro da Junta de Governadores da AIEA.

O Brasil não é, no entanto, membro permanente da Junta de Governadores, embora a integre desde sua criação. Segundo o Prof. José Israel Vargas (Vargas, 2007) o Brasil teve sua posição permanente na Junta de Governadores da AIEA contestada pelos EUA que queria a alternância de Brasil e Argentina nessa representação. Ainda segundo o Prof. Vargas[9], o Brasil acabou renunciando à vaga reservada ao país mais avançado na região, quando parecia estar assegurada sua eleição pelo voto, em virtude de instrução do embaixador Santiago Dantas, na época Ministro de Relações Exteriores do governo João Goulart. A decisão envolveu a adoção de um sistema de rodízio entre Brasil e Argentina no posto reservado ao país com maior desenvolvimento na região que ocupa uma vaga das seis reservadas à América Latina, dentro do sistema de proporcionalidade da ONU. O Brasil e Argentina se alternam em uma das vagas preenchidas por eleição entre os países da Região. Isto, segundo o embaixador Laércio Vinhas, é determinado por um “acordo de cavalheiros” entre os países da região[10] na década de sessenta. Os outros disputam, a partir daí, as restantes quatro vagas. Neste arranjo, Brasil e Argentina vêm assegurando sua presença na Junta, o Brasil desde o início e a Argentina desde 1961.

Em todo caso, a presença do Brasil na Junta de Governadores não é uma posição que o País possa abrir mão. Também é importante que não se aceite a imposição de dificuldades adicionais ao direito de cada parte de retirar-se do Tratado. Este tipo de proposição, na verdade, já existe e tornaria praticamente irreversível a adoção do TNP; assim como existem propostas de tornar obrigatórias as salvaguardas ampliadas no modelo do Protocolo Adicional que o Brasil, com muita razão, se recusa a assinar[11].

No entanto, mesmo que um país não tenha esse direito de veto, ele não pode ser obrigado a aceitar uma cláusula do novo contrato que não foi pactuada por ele. Isto poderia justificar, inclusive, sua retirada do Tratado. Com efeito, o artigo X §1 prevê a denúncia do Tratado face a “acontecimentos extraordinários, relacionados a esse Tratado, que ponham em risco seus interesses supremos”. É claro que a retirada de um país do TNP não é, na prática, um ato sem consequências como deveria ser o simples exercício de um direito assegurado no Tratado.

Pode-se pensar que uma emenda ao TNP que modifique substancialmente a obrigação das partes deveria requerer uma aprovação de cada país para ser nele colocada em vigor. O Tratado não prevê essa possibilidade e isso teria que ser expresso com a denúncia do Tratado pelo país já que não está prevista a possibilidade da versão antiga do Tratado continuar em vigor para o Estado Membro que não concorde com a modificação.

.

A Conveniência de Ratificar o TPAN

O Brasil propôs e assinou, em 2017, o Tratado sobre a Proibição de Armas Nucleares – TPAN. É um tratado no qual o Brasil e os demais signatários assumem os mesmos compromissos do TNP de forma unilateral e deixam aos demais países a oportunidade de aderir ao Tratado, inclusive os armados. O TPAN deixa ainda mais clara a vedação a qualquer país de manter ou receber armas nucleares em seus territórios. Esta proibição, na verdade, já existe no TNP, mas tem sido sistematicamente violada pelos países nuclearmente armados, mormente os EUA[12], que mantém atualmente armas nucleares na Alemanha, Bélgica, Países Baixos, Turquia e Itália (Kristensen, 2019), pelo menos, sem mencionar a forma que é operacionalizado o “guarda-chuva” nuclear americano para a proteção de Coreia e Japão[13]. Isto apesar do compromisso dos NWS (artigo I)[14] de não transferir armas nucleares ou outros dispositivos nucleares explosivos para outros receptores. As armas da antiga União Soviética foram, aparentemente, desativadas ou transferidas para Rússia e não constam mais da listagem de organizações que se encarregam de fornecer as informações existentes sobre armamentos nucleares.

Enquanto isso, devemos ratificar o Tratado sobre a Proibição de Armas Nucleares – TPAN (UN, 2017) e trabalhar por sua colocação em vigor pelos outros países. O Brasil liderou, juntamente com África do Sul, Áustria, Irlanda, México e Nigéria, o processo que resultou em sua aprovação pela Assembleia Geral das Nações Unidas por 122 votos a favor com um voto contra (Países Baixos) e uma abstenção (Singapura) em agosto de 2017. Significativamente, os países possuidores ou hospedeiros de armas nucleares se negaram a participar da Assembleia, com exceção dos Países Baixos (Holanda). Sessenta e nove países, entre os quais os países nucleares e seus aliados da OTAN não compareceram. Essa posição é justificada por uma pretensa oposição do TPAN ao regime TNP. Na verdade, o TPAN, tecnicamente, não se opõe em nada ao TNP já que os signatários assumem todos os compromissos contidos no TNP. A diferença fundamental é que os signatários não reconhecem a posição privilegiada dos integrantes do P5 nem a dos que dão permissão de instalação de armas nucleares em seus territórios.

O Presidente Temer, comparecendo à cerimônia de assinatura, tendo sido o primeiro a firmar o Tratado, reforçou a importância da iniciativa. O TPAN deve ainda ser ratificado pelo Congresso. O Brasil, inclusive, recebeu um prêmio da Associação pelo Controle de Armas por sua liderança no processo[15].

Em nota na ocasião da Assinatura do Tratado, o Itamaraty afirmou que “A comunidade internacional já baniu as outras armas de destruição em massa, químicas e biológicas. Não há motivo para não buscar proibir, igualmente, as armas com maior poder destrutivo, capazes de exterminar a vida na Terra”.

O TPAN não acrescenta nenhum novo compromisso aos países não nucleares membros do TNP e, no caso do Brasil e Argentina, àqueles que já são objeto do Acordo Bilateral. Ele apenas reforça a determinação da Sociedade Brasileira, estabelecida na nossa Constituição Federal, de usar a energia nuclear apenas para fins pacíficos.

Sua desejada ratificação será a reafirmação da posição brasileira de liderança na defesa desse princípio e do amplo direito dos países ao uso da tecnologia nuclear para fins pacíficos, incluída a propulsão naval.

O TPAN não se opõe ao TNP, tem a vantagem de não ser discriminatório e cria uma maior pressão pelo desarmamento. A razão da oposição que ele hoje enfrenta não pode ser associada à atual redação do TNP, mas a novas cláusulas ainda mais restritivas que os países direta ou indiretamente protegidos pelas armas nucleares queiram impor, nas revisões periódicas do TNP, aos países não nuclearmente armados. Esta é mais uma razão para que o Congresso Brasileiro acelere os procedimentos de ratificação do TPAN.

Abreviaturas

ABACC – Agência Brasileiro-Argentina de Contabilidade e Controle de AIEA – Agência Internacional de Energia Atômica

EUA – Estados Unidos da América,

FHC – Abreviatura do nome do Presidente Fernando Henrique Cardoso

NSG – Nuclear SuppliersGroupgrupo de países supridores (de equipamentps) nucleares,

Materiais Nucleares,

NWS – Países reconhecidos como possuidores de armas nucleares,

NNWS – Países não possuidores de armas Nucleares, no âmbito do TNP,

ONU – Organização das Nações Unidas,

OPANAL – Organismo para a Proscrição das Armas Nucleares na América Latina e no Caribe

OTAN – Organização do Tratado do Atlântico Norte,

P5 – Grupo de países integrantes permanentes do Conselho de Segurança, com direito a veto e reconhecidos como possuidores de armas nucleares pelo TNP,

TNP –(em inglês NPT) Tratado de Não Proliferação Nuclear,

TPAN – (em inglês, TPNW) Tratado sobre a Proibição de Armas Nucleares,

Tlatelolco – Nome da região mexicana onde foi assinado o Tratado para a proscrição das Armas Nucleares na América Latina e no Caribe, Tratado de Tlatelolco.

Bibliografia

Kristensen, H. M. (29 de apiril de 2019). United States nuclear forces, 2019. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 75:3, pp. 122-134.

Opanal Inf. 14. (2015). Tratado de Tlatelolco. Fonte: OPANAL: http://www.opanal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tratado-Tlatelolco_port.pdf

Panda, A. (17 de july de 2018). No First Use’ and Nuclear Weapons. Acesso em dec de 2019, disponível em Foreign Affairs: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/no-first-use-and-nuclear-weapons

- (2015). Non-Proliferatopn of Nuclear Weapons – Text or Treaty. Fonte: 2015 Review Conference of NPT: https://www.un.org/en/conf/npt/2015/pdf/text%20of%20the%20treaty.pdf

- (july de 2017). Treaty on the Prohibition on Nuclear Weapons. Fonte: United Nations conference to negociate a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons leading towards teir total elimination,: https://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8

Vargas, J. I. (2007). Ciência em tempo de crise 1974-2007. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

[1] O TNP foi assinado em 1º de julho de 1968, mas só entrou em vigor em 1970, em 2018 foi comemorado o cinquentenário de sua assinatura.

[2]NWS, Nuclear Weapons States e NNWS Non-Nuclear Weapons States.

[3] Article VI “Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”Tradução oficial: Cada Parte deste Tratado compromete-se a entabular, de boa fé, negociações sobre medidas efetivas para a cessação em data próxima da corrida armamentista nuclear e para o desarmamento nuclear, e sobre um Tratado de desarmamento geral e completo, sob estrito e eficaz controle internacional.

[4] All the Parties to the Treaty undertake to facilitate, and have the right to participate’«in,the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials and scientific and technological information for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.(Article V §2)

Tradução oficial: Todas as partes deste Tratado comprometem-se a facilitar o mais amplo intercâmbio possível de equipamento, materiais e informação científica e tecnológica sobre a utilização pacífica da energia nuclear e dele tem o direito de participar.

[5] O chamado Clube de Londres, deu origem ao Nuclear SuppliersGroup – NSG, o grupo reuniu inicialmente os P5 + Canadá e Alemanha Ocidental e, paulatinamente, se estendeu a outros supridores, inclusive o Brasil. Controla a exportação não só de equipamentos de usos nucleares, mas também de usos duais.

[6] O Acordo Bilateral Brasil-Argentina é pioneiro ao proscrever o uso de explosões pacíficas que até hoje é permitido no TNP a países não nuclearmente armados por intermédio dos armados, trata de forma conveniente a preservação do direito ao uso de tecnologias para usos pacíficos da energia nuclear e resguarda a posição histórica dos dois países contra medidas discriminatórias.

[7] Ratificação em 18 de setembro 1998 http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/D2864.htm

[8]Any amendment to this Treaty must be approved by a majority of the votes of all the Parties to the Treaty, including the votes of all nuclear-weapon States Party to the Treaty and all other Parties which, on the date the amendment is circulated, are members of the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

[9].O Brasil fazia parte do grupo dos países mais adiantados, “devido a sua participação ativa e independente, bem como seu grau desenvolvimento, desde os primórdios da era nuclear. Nosso País, entretanto, teve contestada pelos Estados Unidos sua condição de país mais avançado da região: o governo doe EUA propôs que nossa participação na (Junta da) AIEA fosse alternada com a Argentina. Para isso designou um Comitê de três membros, presidida pelo físico Gunnar Randers para ouvir as delegações” dos dois países. Ele integrava a brasileira, chefiada pelo Prof. Marcelo Damy de Souza Santos e a delegação argentina era chefiada pelo Alte. Quihullait. “Como era fácil prever, a comissão técnica não chegou a qualquer resultado devolvendo o assunto à Junta. Segundo o regulamento da Agência, a decisão seria obtida através de votação. A avaliação dos votos sugeria provável vitória do Brasil, que, no entanto, foi impedida de realizar-se pela renúncia de nossa candidatura”.

[10]Relatório de Gestão Missão Permanente do Brasil junto à Agência Internacional de Energia Atômica, em Viena, Embaixador Laercio Antonio VinhasDOC-Anexo-20160905legis.senado.leg.br › sdleg-getter › documento: “Órgão de decisão política da AIEA, a Junta de Governadores da AIEA é integrada por 35 Estados Membros, que são eleitos ou designados. Estes últimos são escolhidos segundo critérios estabelecidos no Estatuto da AIEA com base no seu nível de desenvolvimento nacional na área nuclear. Desse modo, os países mais desenvolvidos nesse campo estão sempre presentes na Junta como designados. Com base em “acordo de cavalheiros” a que chegaram com os países de nossa região no início da década de 1960, Brasil e Argentina, os dois países com os programas nucleares mais desenvolvidos na América Latina e Caribe, integram a Junta de Governadores ininterruptamente (o Brasil desde a criação da Agência, e a Argentina a partir de 1961). Cada um dos dois países integra o órgão por dois anos como membro designado e, no biênio seguinte, como eleito. Outros países da região são eleitos para as demais quatro vagas correspondentes à região, com mandatos de dois anos.

[11]Ver, por exemplo proposta do Vice-Presidente do Geneva International Peace Research Instituteem http://ceness-russia.org/data/page/p301_1.pdf

[12] Os membros da OTAN, usando argumentos técnicos sobre o efetivo controle das armas nucleares contestam essa violação com interpretações do conceito de transferência, como por exemplo, em https://web.archive.org/web/20150128114502/http://www.opanal.org/Articles/cancun/can-Donnelly.htm

[13] A respeito da situação na Coreia ver A desnuclearização das Coreias (Feu Alvim, C.; Mafra, O. e Vargas, J. I.) http://eee.org.br/?page_id=2361

[14] Article I Each nuclear-weapon State Party to the Treaty undertakes not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly; and not in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any non-nuclear-weapon State to manufacture or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, or control over such weapons or explosive devices.

[15] A “Arms Control Association” (ACA) agraciou as delegações de desarmamento do Brasil, África do Sul, Áustria, Irlanda, México e Nova Zelândia e a embaixadora ElayneWhyte Gómez (Costa Rica) com o prêmio “Arms Control Persons of theYear” pela liderança nas negociações que levaram à adoção do Tratado para a Proibição de Armas Nucleares (TPAN).http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/pt-BR/notas-a-imprensa/18175-premio-concedido-ao-brasil-pela-associacao-de-controle-de-armas